I Lost My Sin Number What Do I Do

Hate the Sin, Not the Book

Reading works from the past can offer perspective—even when they say things we don't want to hear.

About the author: Alan Jacobs is a professor of humanities at Baylor University.

This might seem a very strange time to publish a book recommending that we read the voices from the past. After all, isn't the present hammering at our door rather violently? There's a worldwide pandemic; a presidential election is about to consume the attention of America; and if all that weren't sufficient, we are entering hurricane season. The present is keeping us plenty busy. Who has time for the past?

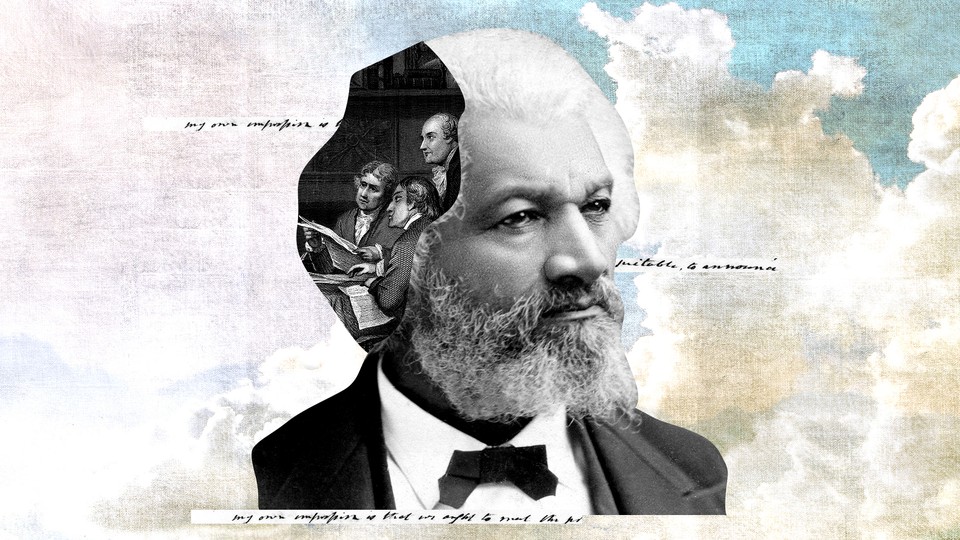

But my argument is that this is precisely the kind of moment when we need to take some time to step back from the fire hose of alarming news. (When I first tried to type fire hose, I accidentally typed dire hose instead. Indeed.) As we try to manage our dispositions, we need two things. First, we need perspective; second, we need tranquility. And it's voices from the past that can give us both—even when they say things we don't want to hear, and when those voices belong to people who have done bad things. One of the best guides I know to such an encounter with the past is Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave, America's most passionately eloquent advocate for the abolition of slavery.

In Rochester, New York, on July 4, 1852, Douglass gave a speech called "The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro," and it is as fine an example of reckoning wisely with a troubling past as I have ever read. He begins by acknowledging that the Founders "were great men," though he immediately goes on to say, "The point from which I am compelled to view them is not, certainly, the most favorable; and yet I cannot contemplate their great deeds with less than admiration." Yes: Douglass is compelled to view them in a critical light, because their failure to eradicate slavery at the nation's founding led to his own enslavement, led to his being beaten and abused and denied every human right, forced him to live in bondage and in fear until he could at long last make his escape. Nevertheless, "for the good they did, and the principles they contended for, I will unite with you to honor their memory."

What, for Douglass, made the Founders worthy of honor? Well, "they loved their country better than their own private interests," which is good; though they were "peace men," "they preferred revolution to peaceful submission to bondage," which is very good, and indeed true of Douglass himself; and "with them, nothing was 'settled' that was not right," which is excellent. Perhaps best of all, "with them, justice, liberty and humanity were 'final'; not slavery and oppression." Therefore, "you may well cherish the memory of such men. They were great in their day and generation."

David Blight: Frederick Douglass's vision for a reborn America

In their day and generation. But what they achieved, though astonishing in its time, can no longer be deemed adequate. Indeed, it never could have been so deemed, because they did not live up to the principles they so powerfully celebrated. They announced a "final"—that is, an absolute, a nonnegotiable—commitment to justice, liberty, and humanity, but even those who did not own slaves themselves negotiated away the rights of Black people. And so Douglass must say these blunt words: "This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn."

I wonder whether I can even imagine what it cost Douglass to speak as warmly as he did of the Founders. In his autobiography, he describes a moment when he was 12 years old and came across a book containing a fictional dialogue between a slave and his owner. "The more I read, the more I was led to abhor and detest my enslavers. I could regard them in no other light than a band of successful robbers, who had left their homes, and gone to Africa, and stolen us from our homes, and in a strange land reduced us to slavery. I loathed them as being the meanest as well as the most wicked of men." The Founders could not have been exempt from this loathing: After all, many of them owned slaves, and others tolerated their slave-owning, They deserved denunciation no less than the men who had claimed ownership of Douglass. And yet, in his Rochester speech, he conquered his indignation sufficiently to say: "They were great in their day and generation."

Decades ago, I read an essay by a feminist literary critic named Patrocinio Schweickart about how feminists should read misogynistic texts from the past. She counseled them to face the misogyny but also to look for what she called the "utopian moment" in such texts, an "authentic kernel" of human experience that can be shared and celebrated. I think that's what Douglass does. He has every reason, given what their sins and follies cost him and his Black sisters and brothers, to dismiss the Founders wholly, but he does not. "They were great in their day and generation."

It would be utterly unfair to demand of anyone wounded as Douglass was wounded the charity he exhibits here. I would not ever dare to ask it. That he speaks as warmly of the Founders as he does strikes me as little less than a miracle. But this fair-mindedness was integral to Douglass's massive success as an orator, as a persuader of the half-convinced and the faint of heart. He knew how to sift, to assess, to return and reflect again. The idealization and demonization of the past are equally easy, and immensely tempting in our tense and frantic moment. What Douglass offers instead is a model of negotiating with the past in a way that gives charity and honesty equal weight. This is why I say that, when confronted by the sins of the past, Frederick Douglass should be our model.

Clint Smith: Taking my children to see Frederick Douglass

Reading those figures from the past, even when he disagreed strongly with them, gave him some perspective on his own moment, and, because they left this vale of tears, some tranquility as well. After all, the dead don't talk back to us—unless we invite them to. We control the encounter. We decide whether to pay our ancestors attention.

When we make that payment, when we turn aside from the "dire hose" and take a few deep breaths and enter into the world of the past, we can calm our pulse a bit, take time to think. No one demands anything of us. Those figures from the past are willing to speak to us when we are willing to listen. They may sometimes speak words of offense, but they may also speak words of wisdom that we either never know or have forgotten.

Two thousand years ago, the Roman poet Horace wrote a verse letter to a friend. "Interrogate the writings of the wise," he advised, "Asking them to tell you how you can / Get through your life in a peaceable tranquil way." It was good advice then and it's good advice now.

This post is adapted from Jacobs's recent book, Breaking Bread With the Dead: A Reader's Guide to a More Tranquil Mind.

I Lost My Sin Number What Do I Do

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/09/hate-sinner-not-book/616066/

0 Response to "I Lost My Sin Number What Do I Do"

Post a Comment